#BrusselsBookCity: Among the Missing

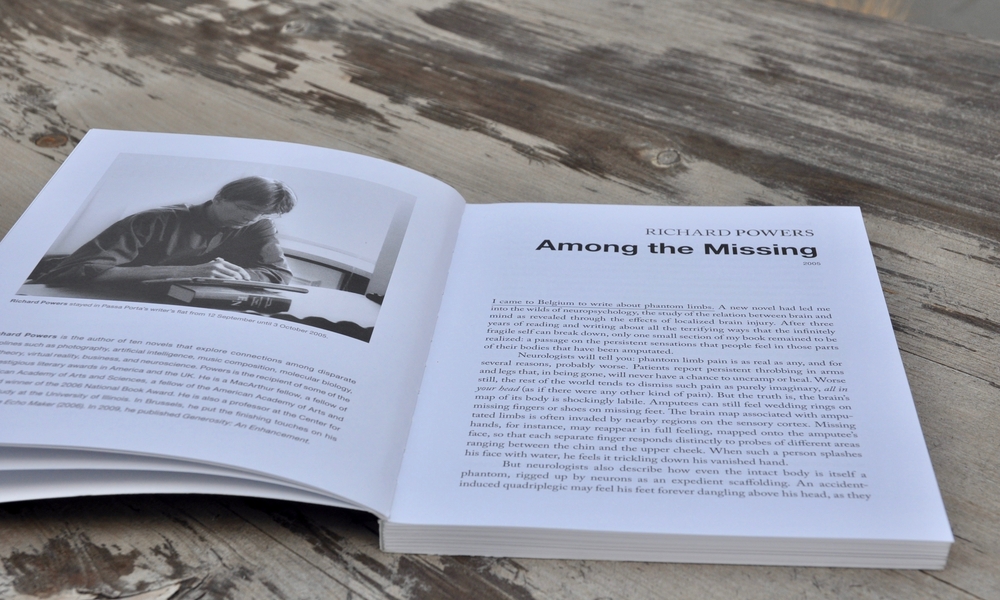

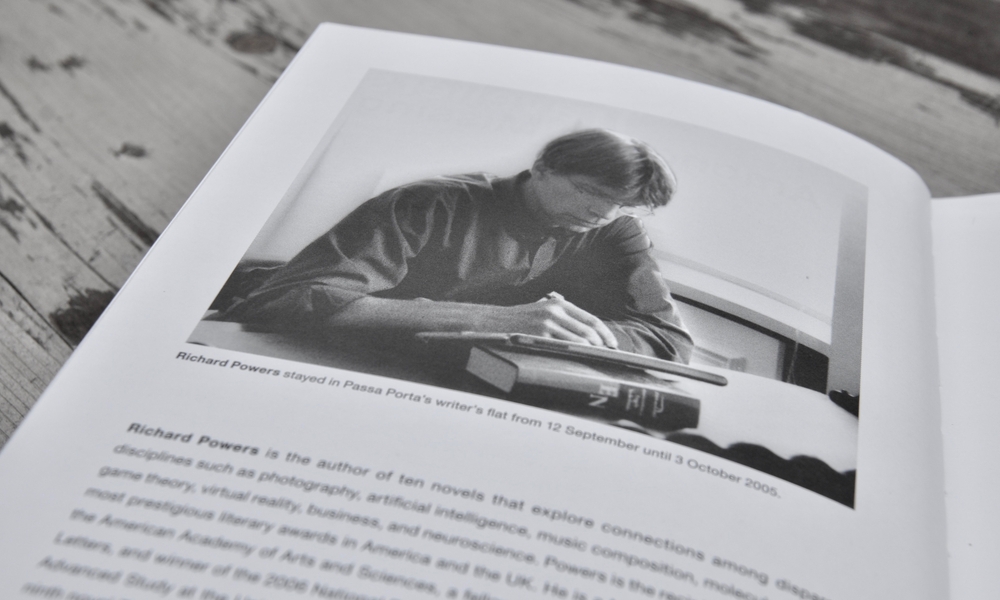

Richard Powers schreef deze tekst na zijn verbijf als Passa Porta's schrijver in residentie in 2005. De tekst verscheen eerst in Writing Away from Home, International Authors in Brussels, Cahier Het beschrijf, 2010. Ontdek hoe de stad na zijn vertrek aanvoelde als verdwenen ledematen.

I came to Belgium to write about phantom limbs. A new novel had led me into the wilds of neuropsychology, the study of the relation between brain and mind as revealed through the effects of localized brain injury. After three years of reading and writing about all the terrifying ways that the infinitely fragile self can break down, only one small section of my book remained to be realized: a passage on the persistent sensations that people feel in those parts of their bodies that have been amputated.

Neurologists will tell you: phantom limb pain is as real as any, and for several reasons, probably worse. Patients report persistent throbbing in arms and legs that, in being gone, will never have a chance to uncramp or heal. Worse still, the rest of the world tends to dismiss such pain as purely imaginary, all in your head (as if there were any other kind of pain). But the truth is, the brain’s map of its body is shockingly labile. Amputees can still feel wedding rings on missing fingers or shoes on missing feet. The brain map associated with amputated limbs is often invaded by nearby regions on the sensory cortex. Missing hands, for instance, may reappear in full feeling, mapped onto the amputee’s face, so that each separate finger responds distinctly to probes of different areas ranging between the chin and the upper cheek. When such a person splashes his face with water, he feels it trickling down his vanished hand.

But neurologists also describe how even the intact body is itself a phantom, rigged up by neurons as an expedient scaffolding. An accident-induced quadriplegic may feel his feet forever dangling above his head, as they were at the moment when his spinal cord was damaged. Stroke victims will sometimes claim they have two left arms, or even an extra neck and head. We do not live in our muscles and joints and sinews; we live in the thought and the image and the memory of them.

All this is what I came to Belgium to write about. Why Belgium? Why leave the sheltering emptiness of the American Midwest at all, when its level, unbroken cornfields had been so conducive to the composition of the rest of my novel? Because it seemed to me that this final section of my story — this short interlude on phantom pain — held the key to a small secret about the self, a fact about belonging in this world that we are forever too familiar with to see. The truth is: the body is the only home we ever really have, and even it is more a postcard than a place. ‘Home’, as Stefan Hertmans writes, ‘is the place where the world around us becomes invisible.’ And so we must leave it, to render it real again.

I had to leave home to finish my story, but I couldn’t go just anywhere. I chose to go to a place that I once almost knew intimately, a place I once imagined myself living in forever, although I never came closer than briefly living next to it. I wanted to put to the test my memories of a country that had felt so strangely and undeservedly familiar to me, on the many trips I made there, a dozen years ago: my Belgium, a Belgium that was, like the castle-stubbed rolling landscape in the background of a Flemish primitive painting, always more the work of the artist’s imagination than of empirical fact. What better place to write about the persistent pain of limbs long ago removed?

Through the generosity of Passa Porta, I and my wife, who had never before stepped foot in the Low Countries, found ourselves in a brilliant apartment on the Oude Graanmarkt, she to work on the translation of a novel out of French, and I to complete a novel about the improvised treachery of the self. Everything I had told my wife in anticipation of this trip turned out to be wrong. I’d prepared her for the drizzly, dank Septembers of my memory. Instead, we were disoriented by three straight weeks of blazing Italian sunlight. I’d told her to expect a quaint and slightly diffident Flanders that shut down every day from twelve to two for lunch. The Flanders we landed in, brutally streamlined by European integration and facing its own rising tide of xenophobia, had grown almost sleek.

‘Memory’, Kundera argues, ‘is not the opposite of forgetting; it is a kind of forgetting.’ And my memory of Belgium was not above playing all of the expected rearrangement tricks of a decade and more of absence: the streets that now ran in different directions, the buildings that had changed shape and size. Leuven had come glittering from out beneath a coat of grime. Gent had turned into Bruges, and Bruges had devolved into a perfect simulacrum of itself. Onze-Lieve-Vrouw in Antwerp and Sint-Michiels in Brussels, decapitated hulks when I’d last prowled around them, had returned as pretty, gothic ghosts.

Wandering around Brussels’s Square Ambiorix late one afternoon in search of a forgotten Art Nouveau façade, we stumbled upon the corner of a spanking new building that somehow seemed both unrecognizable and weirdly familiar. It was some minutes before I placed it: a face-lifted Berlaymont, wrapped in a skin of bullet-proof glass and anti-terrorist (or anti-demonstrator) baffles, like some massive arthropod that, rather than shed its chitinous exoskeleton, had crawled back inside it. Memory might be a kind of forgetting, but progress, so eager to forget, never travelled very far.

I made the whole cross-country tour, every town both killing and reviving something lost in me. I spent three weeks struggling to recover a language that I had spoken quite comfortably once, managing to sound, on good days, something like Vandersteen’s Jerom at his most stoic. My appetite for phantom pain had no limit. We weathered the country’s 175thbirthday, which seemed to pass in a mixture of pride, anxiety, and indifference. We rode the trains everywhere, sitting across from packs of schoolchildren with Memling faces on their way to a sunny weekend in Ostend. We stood inside a Tournai cathedral turned into a Magritte by scaffolding and excavations. My wife photographed me, rappelling down the tower of St. Vincent in Soignies, participating in a local fund-raiser. But then, the camera is no more reliable a memory device than is the body.

We found ourselves at one point in the legendary basement of the Africa Museum in Tervuren, poking around the remnants of collections that would never go out in front of the public, but would forever sit throbbing in storage. Upstairs, the Memory of the Congoexhibit was prompting a national debate that broke down, to no one’s surprise but the outsider, along language lines. What still needed saying about that past? What couldstill be said? Were the amputated hands of the Congolese in the old photographs atrocities or gangrene? And why did the whole world still feel them, so long after their removal?

It surprised me to read, in the battered Blue Guide that we dragged all across the country, that far and away the vast majority of Belgian tourism was aimed at battlefields. It never occurred to us to stop in Waterloo, on our way to Nivelles. We did not have the heart for Ypres. Mechelen seemed more compelling a destination than Bastogne. And yet, on reflection and after a harder look, the fact was self-evident. Half the buildings in this country are what they are only through amputation – destroyed and rebuilt, never what they started as, never entirely new. We travel to recover something vanished in us, and find only what the present has been able to salvage and renovate, since the latest war.

So we chased through Belgium, a country plagued by the past, hard-pressed by the present, and hurtling toward a future that, as always, it will never survive. And so, by traveling there, I remembered how I might finish my book: we know ourselves by the parts we thought we’d lost.

I write this from a small Midwestern town, a week after coming back to a newly strange home. The feel of the Oude Graanmarkt still throbs a little, in my body. I will be back again, without doubt. Belgium, of course, will be long gone by then. But then again, so will this I.

Richard Powers keert in september terug naar Brussel voor Festival America Brussels. Mis hem niet!