Public Message (8) The Language of Our Time

‘Social distancing’ is what Corona experts advise, but ‘social nearness’ is what we aim for with our literary events. Passa Porta wants to keep connecting authors with their readers. Over the coming weeks, we will therefore be asking writers, from home and beyond, for a personal “Public Message”.

In between housework and homeschooling his children, Brussels-based Eritrean novelist Sulaiman Addonia wrote a plea for self-exploration and urges his readers to embrace the language of silence in these times of self-isolation.

-

In 2009, as I started my second novel, Silence is My Mother Tongue, I would wake up in the middle of the night, sit up with my back against the wall and stare into the sea of blackness surrounding me. Silence, laying in that dark place, invited me to return to its fold again and again. The night had become a silent listener of my unuttered thoughts and unspeakable dreams, where I felt at home with all my characters, even those who took me to dark places, because we were speaking the same language: Silence.

But if Silence were a language then how do we master it, expand our vocabulary, so that we can speak it fluently? And who gets to design its grammar? Although I have no answers to any of these questions and my investigation is still ongoing, in my view, we don’t acquire Silence through our mothers, or societies, or schools, it is perhaps the only language innate to us all, with which we are all born.

To be silent, is to be naked of a spoken language, of an identity, religion, morality, societal conditioning, nationality and nationalism — perhaps to be silent is the closest one can come to realising what it means to be a human being, in the primitive, noble sense.

Silence is the only common language that unites natives and immigrants, men and women, children and adults. It has always been a universal language. A language that many of us have been taught to suppress but that art can revive.

Truly. Art has the ability to allow people to rediscover the beauty of our universal language. In the way Gabriel García Márquez wrote in Love in the Time of Cholera:

Like novels, cinema played a key role in shoring up my confidence to not only understand silence but embrace it as my mother tongue. I remember it was a Japanese film, Hana-bi, by director, actor Takeshi Kitano, released in 1997 in which I first felt silence spoken as a language in cinema, the lead actor going through the film without speaking much. The silent moments by far outweighed the spoken ones. Silence as a language breathed in the film, it had the entire landscape to roam, the sea, the mountains. It profoundly stood out and it made the film one of the most memorable ones for me. And because dialogue was far and in between, this silence allowed me to enjoy other elements that we are often distracted from when we have actors continuously engaged in conversations. I could see the interior, pay attention to the faces of the people in the film, follow the gazes of their eyes, read the details of feelings in their features, so that even a slight movement of the muscles in Takeshi Kitano’s face would be noticed.

That is what Silence as a language does, it invites you to listen beyond the words spoken by characters and listen to their bodies, listen to their feelings, become a witness to their interior and exterior emotions. Silence, in other words, is, in my view, the most suitable language for art. And to handle it skilfully is, as Charles Baudelaire wrote, to practice a kind of evocative sorcery.

I sometimes read poems, without understanding, but I still feel their power in my core. Some poets, I always sensed, have a way of bypassing the intellect to speak directly to the soul. And to me, the language of the soul is Silence.

Silence allowed me, as an artist, to break out of history, of talking, of plentiness, of explanations, of plot, of perceptions, of traditions, religions, and taboos. It made me feel absolutely free, in the way Marguerite Duras wrote,

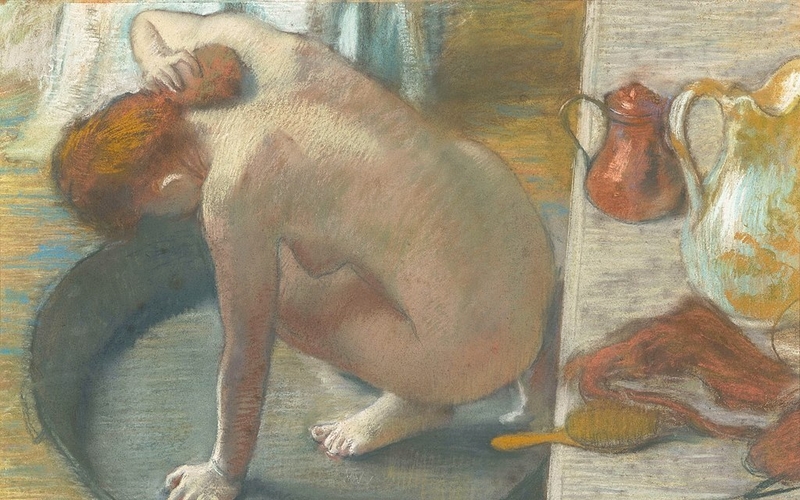

Although Silence is a language that is difficult to master, it perhaps should be one of the things people learn in these self-isolating times, given the beauty and freedom it brings. The more we look at paintings that figure silence like Edgar Degas’s bath series, that inspired Silence is My Mother Tongue, read a novel such as Gabriel García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold, or listen to music like Beethoven’s Silence by Ernesto Cortázar, we will be encouraged not only to value it, but hear it and embrace it.

Sulaiman Addonia, Brussels, April 2020