Afterthought: Close-reading Aleksandra Lun's "antimatter"

In true Brussels fashion, sixteen readers are seated behind their screens – a predicament all are now well familiar with – and introduce themselves in Flemish, Polish, British and ambiguously European accents. They are gathered during the Passa Porta Festival to take a close read of Aleksandra Lun’s newly commissioned essay, ‘Antimatter’, as part of Brussels International, a project that seeks out literary authors based in the capital who write in languages other than Belgium’s linguae francae.

Lun wrote the original ‘Antimateria’ in her literary tongue, Spanish, a language that visited her later in life. The linguistic encounter also gave rise to her tragi-comic novel The Palimpsests*, which tells the absurdly funny and unsettling story of an Eastern-European author, Czesław Przęśnicki, whose love for the Antarctic language leaves him stranded in a psychiatric asylum in Liège, Belgium. There, he undergoes a treatment forcing him to renounce his foreign tongue and return to his ‘native’ Polish. Unlike her latest novel, however, 'Antimatter' takes on the form of what the author calls “an essay that is a short story written as a poem” to delve deeper into the process of writing in foreign languages, and the kinds of political and literary forms of (un)belonging it generates.

The Somnambulist Writer

“The boundary between waking and sleeping is where creativity happens,” Lun tells her online audience during the close-reading. She is referring to the nameless somnambulist author narrating ‘Antimatter’, whose arms stretch before them as they carefully straddle the line between sleeping and waking, “the only border in writing”. Lun and the sleepwalker tell us that life is fiction, and call upon Jerzy Pilch’s idea that all literature is an archive of dreams; even the most realistic novel is simply a dream conveyed with more precision. The image of the somnambulist captures this double experience of presence and absence that guides creative endeavours, not quite certain what it is that drives us forward.

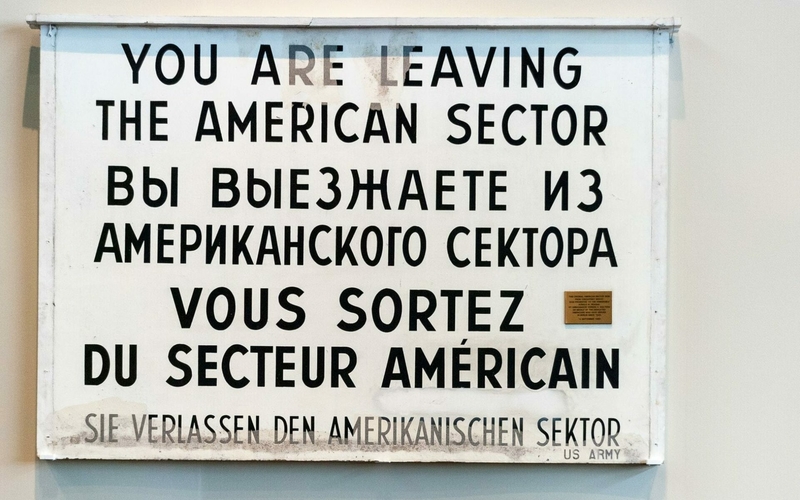

There are other kinds of borders that, put bluntly, make no sense at all. Geopolitical borders, Lun writes, are a “game of chance”, a “roulette ball” set in motion by History itself. The ball gravitates from the centre to the periphery – a nod to Immanuel Wallerstein’s World-systems theory developed in the Cold War era – and arbitrarily assigns mother tongues at birth. Some win and others lose at the game of national identity. What remains is a sense of belonging that has no substance, or, as the somnambulist expresses: “a fragile ‘I’ wrapped in a national flag”.

Passports as prisons

With a Polish mother tongue, Lun knows one or two things about the porosity of national boundaries. On her screen, she gestures to borders “flying all over the place”. She tells the audience that her experience of border-crossing, from Eastern to Southern and Western Europe, adopting foreign languages along the way, has been an important impetus for her literary journey. In ‘Antimatter’, she conveys that life is fiction, and so are passports; but unlike the somnambulist’s imaginative wanderings, passports and other bordering apparatuses erect administrative prisons that constrict some more than others. And this hostility, or Edward Said’s notion of ‘Othering’, is not only articulated in institutional settings; it also permeates the intimacy of mundane conversation. An audience member explains that under the breath of the violent question ‘where are you from?’ always lies its twin ‘… and when are you going back?’ A few close-readers eagerly nod.

If Lun were to choose her home country, it would be a place called Lunistan, she sardonically tells the audience, “and I will be its dictator!”. Her cutting remark encapsulates the impossibility of fully feeling at home in a nation or language… but that discomfort also becomes a generative force. A foreign language is a catalyst for change that offers new modes of inhabiting the world. This state of being in-between linguistic registers makes us see what we are and what we are not: “in each language we are a different person,” Lun writes. The ‘Other’ (language) has a mirroring effect: it says more about who stands opposite it, than about itself.

In reflecting on my own linguistic situation – a French mother tongue, a Flemish father tongue, the incomprehensible Hungarian tongue of my late grandfather, and the English language I’ve come to inhabit while studying at a Scottish university – I felt at home with Aleksandra Lun’s understanding of the foreign-ness of language as a generative force. ‘Homing’, a term I borrow from Sara Ahmed and her colleagues’ work on ‘Uprooting/Regrounding’, is perhaps less a matter of rooted identities, than the ongoing process of generating spaces that allow us to jump from one tongue to the other, reaching vantage points from which we can better understand ourselves.

What is most surprising about ‘Antimatter’, is that it is written in a way that gives agency to languages: they watch, ignore, admire, reject us. Lun herself described the experience of writing in Spanish as a ‘love affair’. It goes to show that relationships to language are not only extremely dynamic, but that they also manifest in forms other than letters and words. ‘Antimatter’ evokes oral storytelling, imagery (“Every letter of the alphabet begins with an image”), different cosmologies (“words are born and die in us like distant galaxies”) that lead us to wonder where languages and their antecedent forms are located; are they characters that “observe us from afar,” as Lun suggests, or do they emerge from within us? In his later work, Ludwig Wittgenstein sought to grasp the multiplicitous meanings and uses of words by inquiring into the limits of language itself. The philosopher postulated that all words acquire their meaning through their use in accordance with the collectively constituted rules that make up ‘language-games’. These games are interlaced in broader contexts of everyday sociality, or what he ambiguously called ‘forms of life’.

In this way, Ludwig Wittgenstein held that there is no unifying essence of language; the only possible way we can understand meaning is by observing what it does. It is as arbitrary as it is real, just like the borders and mother tongues in Lun’s essay.

Today, politics of xenophobia emerging in all corners of Europe systematically ‘Other’ migrants, while fetishizing what they conceive of as their ‘authentic’ origins. We find unsettling continuities between past authoritarianisms and the present hostility of societies obsessed with ‘roots’, where identity becomes a matter of racialised and monocultural belonging. Such politics encroach cultural institutions, virtual spaces, and the citizenship regimes that distribute mother tongues. The fortification of borders – both national ones, and those of everyday life – brings multilingualism under threat. In Belgium especially these prospects look rather bleak.

Inhabiting the void

In his study La Double Absence, the Algerian philosopher of migration Abdelmalek Sayad bears witness to the diasporic condition of being absent in two spaces at once; leaving behind one’s point of departure, while being engulfed in the hostility of the destination where ‘otherness’ itself becomes an imposed state of absence. Yet it is also through dialogue in mother tongues of the fatherland and foreign tongues of the ‘mother country’, and all those things unsaid, that Sayad gives voice to the contradictions and intimacies of collective border-crossings. His insightful notion of ‘double absence’ may also help us to grasp the meaning of Lun’s ‘antimatter’:

Lun’s exploration of antimatter becomes a metaphor for the boundary between our tangible aspect and the one that remains fleeting. It suggests that presence and absence are not contradictory forces, but rather, that they complement each other. But antimatter disappears so quickly that the limits delineating its existence have not yet emerged. We are then free to imagine those limits ourselves. “The void,” Lun writes, “is our home”. We inhabit it with our foreign tongues and “antilanguages”. Writers like Lun unconditionally surrender to the unknown, and their novels invite us “to read the tale that precedes any language”.

I have to say that I am somewhat doubtful about Lun’s proposal of the novel as a “stateless oracle,” whose stories exist prior to all national borders and linguistic identities. I would rather align myself with the linguistic anthropologist Paul Kroskrity, who held that all language is a site of power struggle and wrote against the universalist ‘myth of the socio-politically disinterested language user’. Yet, as I familiarised myself with Aleksandra Lun’s œuvre, I came to understand that she does not propose the borderless literary identity as a remedy to the ills of the “roulette of history”. Rather, she urges her readers to engage with their own alterity by trespassing the assigned tongues that exist to reproduce all borders. Hands stretched out, we venture into unfamiliar literary geographies, where the only real border is the one between sleeping and waking.

-

* Lun's novel Los Palimpsestos (original Spanish edition, Minúscula, 2015) has been translated in French by Lori Saint-Martin (Les Palimpsestes, éd. du Sous-Sol, 2018), in Dutch by Lisa Thunnissen (De Palimpsesten, uitg. Pluim, 2020), and in English by Elizabeth Bryer (ed. Godine, 2019).

Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash