300 years of Robinson Crusoe, or the colonist revisited

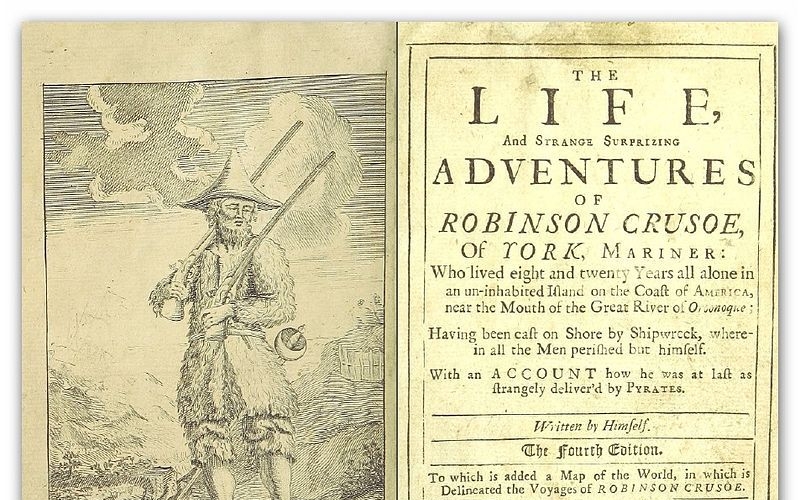

Next spring will mark the 300th anniversary of the publication of Robinson Crusoe (1719). The book, widely considered the first English-language novel, chronicles an unlucky sailor shipwrecked on a deserted island, who carves out a life among wild goats, mutineers, and cannibals.

In honour of Robinson Crusoe’s tricentennial, which will also inspire some of the authors invited to the Passa Porta Festival in March, Delaney Nolan spoke with Prof. dr. Elisabeth Bekers, professor of British and postcolonial literature at VUB. She began by explaining why we can still learn from a book about as old as Mother Goose.

A Pioneer Novel

“It being the first novel in English,” she explained, “you can read the whole of English literary history looking back on that very important moment. It’s a fictional autobiography, so any writer working today and exploring the lives of others, you can tie to Robinson Crusoe.”

This is partly because Robinson Crusoe was groundbreaking in its approach: it virtually launched the genre of realistic fiction. Readers had not seen a detailed, realistic, imaginary account of a life before in book length. It swept the Western world, coined the genre now called “Robinsonade,” and spawned 700+ alternative versions by the end of the 19th century. So Robinson Crusoe was, at the time, a window into literature’s future. But today, we can use it to peer into the past.

The novel “really gives expression to the zeitgeist, the spirit of the era,” Bekers says. That spirit was of course the imperialist, colonialist mindset of the Anglo-Saxons of 1700; the spirit of a man who lands on an island and immediately declares it his own. “It doesn’t cross his mind that it might belong to somebody else. He asks Friday some questions, but not to get to know Friday’s culture, only to get off the island. There’s no discussion with Friday about, ‘What is your religion, what is your culture.’”

Critical and creative responses

James Joyce once claimed Crusoe to be “the true prototype of the British colonist... the manly independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow yet efficient intelligence, the sexual apathy, the calculating taciturnity.” And if Crusoe is the British colonist distilled, then Bekers finds the wealth of postcolonial responses to be the treasure worth seeking. To name just a couple: Foe, by J. M. Coetzee, imagines a female castaway who joins ‘Cruso’ and Friday and struggles to have her tale recorded. Crusoe’s Journal by Derek Walcott frames the natives’ cannibalism alongside the castaway’s belief in transubstantiation.

Texts like these, then, “rewrite the existing records by, for instance, giving voice to enslaved people, by making them the spokesperson — whereas in historical records you don’t find their voices, you find very few traces of their voices, their feelings. So they’re recreating in fiction these people who are invisible to historiography.”

Robinson Crusoe has opened the door for realistic, life story telling in fiction, even as it calls for critical responses to the cultural perspectives it embodies. It’s a 300 year old catalyst that first showed us how one person’s life experience, presented as fiction, can raise questions, present contrasting views, and explore perspectives — not just inform.

The Lives of Others

Bekers adds that the mantle of writing voices currently neglected by the canon should not fall only on the shoulders of like writers. We should share the obligation of amplifying voices — migrant or non-white or female — that have been historically neglected. “That’s one of the reasons I read literature,” she explains. “I want to see how writers imagine the lives of others. If you wanted to read just facts, wouldn’t you just read sociological reports? You can have a lot more nuance in a literary text. If we just reduce these writers to sociological informants, then we are not doing justice to the creative aspect.”